Interview: Theatre Life with Danny Troob

The veteran orchestrator on creating a smaller but no less brilliant set of orchestrations for Signature Theatre's current production of Soft Power and more.

Today’s subject, Danny Troob, has been living his theatre life for over 50 years as an accomplished orchestrator and dance music composer. You can currently hear his orchestral brilliance in Signature Theatre’s production of Soft Power. The show runs through September 15th in The MAX.

Danny’s theatrical credits as an orchestrator include Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella, Big River (co-orchestrator with Steve Margoshes), God Bless You Mr. Rosewater, Romance, Romance (additional orchestrations), The Little Mermaid, and Soft Power at The Public Theatre. However, you are probably most familiar with Danny’s work in both the film and stage versions of Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, Newsies, where he also conducted the songs for the film. He is also the orchestrator for the film and upcoming stage version of Hercules. Read on for more information on that project.

As a composer of theatrical dance music, Danny’s credits include Goodtime Charley and the original production of Pacific Overtures. Both shows were orchestrated by legendary two-time Tony Award winning orchestrator Jonathan Tunick. How lucky can you get?

You might have noticed that much of Danny’s orchestral work is for composer Alan Menken. It’s a collaboration that spans many years, and it’s quite rare for one orchestrator to have that kind of relationship with one composer.

Signature Theatre always hits it when it comes to theatrical timing. Producing Soft Power in an election year is a stroke of artistic brilliance and just solidifies for me why they remain the top theatre for musicals (and plays) in the DMV.

Grab some tickets to Soft Power and hear Jeanine Tesori’s wonderful music as orchestrated by Danny Troob. He is a master of his craft and continues to live his theatre life to the absolute fullest.

Was it always the plan for you to become an orchestrator, or did you think you would always do something in music without knowing what that was?

It was always the plan for me to write music as a composer. I got involved with musical theatre at the lowest level – meaning rehearsal pianist and an associate conductor. I then moved on to dance music, which is composition, and then I became quite a fine orchestrator. Meanwhile, I continued to write shows, but they were not setting the world on fire, and they took a lot of time and love. At about age 40, when my Disney movies began to kick in, I decided I was going to totally focus on orchestration.

Did you have someone that would qualify as your mentor for orchestration?

I would say Jonathan Tunick. I worked on A Little Night Music and some of Pacific Overtures. Later, I worked on Side by Side by Sondheim, which had no orchestrations, just two piano arrangements.

I did other shows with Jonathan that did not involve Sondheim, including Goodtime Charley with Joel Grey. Every time one of our shows opened, he'd give me the orchestral score to an opera and tell me to study it – and I did. He also helped me get early arranging jobs. I think tremendously highly of him.

I had kind of leapfrogged, and orchestrated a Broadway show almost by accident called Sarava by Mitch Leigh. I'm not sure how he got my name, but he called me in for an interview. They were already in rehearsals, and they had a 23-piece band, of whom four were native Brazilian percussionists who didn't read music, but they could read time slashes and rests. He asked me if I wanted the job, and I said “yes, very much.” He said, “you know, many people's faith will be riding on your competence. Do you want the weekend to think about it?” I said, “no, Mitch because I'll come back Monday and just say the same thing.”

What was your first professional job as an orchestrator?

It was for an industrial show for Armstrong Cork. I stayed eleven weeks in Lancaster, Pennsylvania and could take no more. However, the array of orchestrations I had to write went well and it was clear that I could do this. My conducting skills, however, needed more work.

and the cast of Soft Power at Signature Theatre_ Photo by Daniel Rader.jpg)

Signature Theatre's production of Soft Power.

Photo by Daniel Rader.

How did you first get involved with Soft Power?

I've known Jeanine Tesori since 1986 – since the first national company of Big River. I was musical supervisor/co-orchestrator, and she went out as the pianist. Not all that long after that, I orchestrated her first show, which she wrote with her first husband, called Galileo. Since then, if she thinks I’m right for a project, she’ll call me to work on it. Des McAnuff, the director of Big River, does the same.

Can you please talk about how you chose the instrumentation for Soft Power?

Well, there are two sets of orchestrations. There was the one at the Public, which was large and sweeping. It was appropriate for the show that was, at that point, meant as a kind of reverse image of The King and I.

Now the aim of the show is rather different – and the scale of the Signature Theatre production is so much more modest than the Public in terms of the money they have at their command. They wanted eight players, and I got them up to nine. I’m not sure how Jeanine did it, but she got them up to ten, which was as much as they could possibly pay for.

I provided three options for how the show could be orchestrated. There was a possible nine-piece orchestration. Next was called “Most Like Broadway,” which was the most intellectual, the most Stravinskyesque. The third one I called “Kill Em With Class.” I only called it that because I didn't really want to put Into the Woods into an email.

We are mostly using the concepts of the third orchestration. We have a dedicated bassoon chair, which is an enormous luxury, and adds a tremendous amount of interest to the sound of the show. It’s a very classy sounding ensemble.

and the cast of Soft Power at Signature Theatre_ Photo by Daniel Rader.jpg)

Signature Theatre's production of Soft Power.

Photo by Daniel Rader.

In New York, Larry Hochman and John Clancy shared orchestration billing with you. Is their work still intact for this current production?

Larry reduced his two songs for me, and I reduced Clancy’s two charts.

You have a long association with Alan Menken. We all know that his first writing partner, Howard Ashman, passed away way too young. If he were still with us, do you think Menken and Ashman would have been an exclusive writing team?

I think they would have done a lot of great work together. I don't think they'd have been exclusive. While Howard was still well, he did the show Smile with Marvin Hamlisch. I don't think he would have limited himself only to working with Alan, and I think Alan would have wanted to work with other lyricists.

I suspect that their best work would have been with one another for sure, but I don't think it would have been an exclusive collaboration.

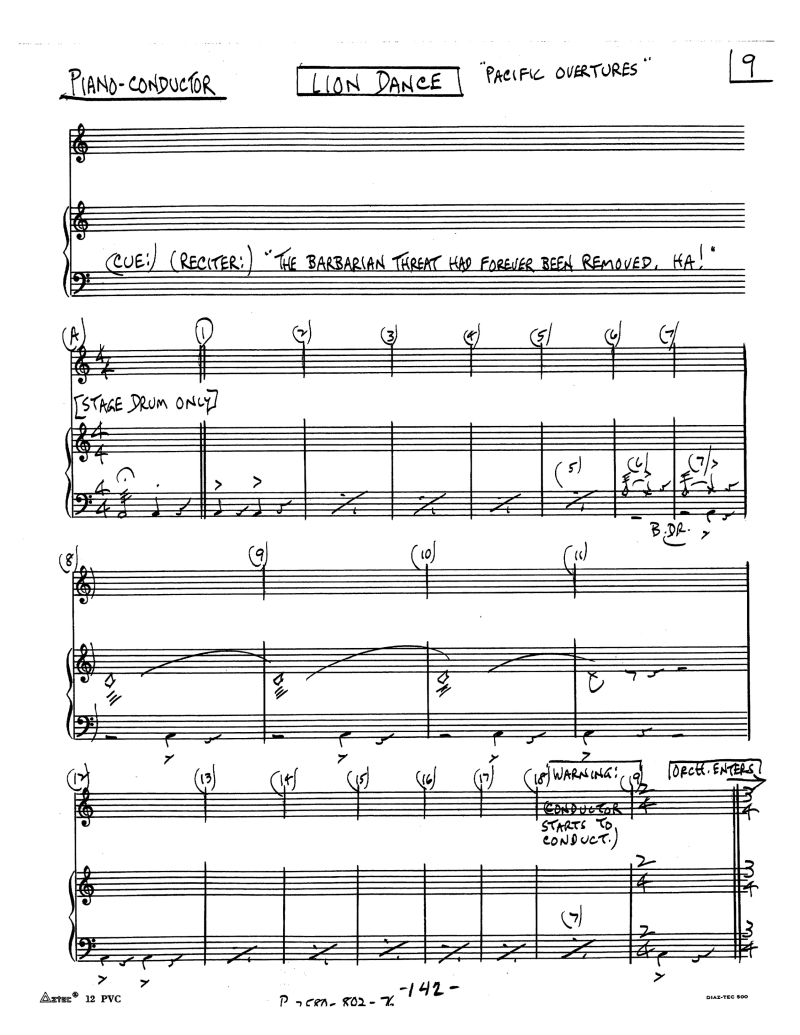

Broadway production of Pacific Overtures as orchestrated by Jonathan Tunick.

Image courtesy of Michael Lavine.

You wrote the brilliant “Lion Dance” music for the original production of Pacific Overtures. Can you please talk about the experience of creating dance music for a Stephen Sondheim musical?

I was ready for it musically. I was not ready for the politics of the situation, which I cannot go into in overly great detail. But I can tell you that, in discussing things, the usual format for conversations was this is an American idea of a Japanese idea of an American idea of a musical. But it needs to be an American idea of a Japanese idea of an American idea of a Japanese idea of a musical. Stephen could think like those mirrors behind you in a barber shop where you'd see your face an infinite number of times. Steven had a fantastically high IQ and could follow those lines of logic in a way that none of the rest of us could. It had a big impact on how the “Lion Dance” got written.

It was an important step and credit for me. Stephen Schwartz hired me to work on The Baker's Wife purely on the strength of Pacific Overtures.

Of all the projects you have worked on in your long and distinguished career, what are a few that stand out as favorites?

My favorite is the one that was the turning point for me, Beauty and the Beast. Alan and Howard had already had a great success with The Little Mermaid, but with a different arranger and a different orchestrator. We had all just turned 40. I called Alan and congratulated him and said, “You know, I know I wasn't on it, but I feel somehow this has to be good for all of us.” I was astonished that I got a call to work on Beauty and the Beast. It was just right in my power alley. It was a little bit pop, and a little bit classical, childlike, and energetic. I killed it. I knew I would as soon as I heard the music.

It was also a nice time in music. Not everything had to be demoed. Not everything had to be mocked up with samples so that executives could weigh in on what they liked and didn’t like.

Beauty and the Beast got thrown together pretty fast, and that was largely because Howard was sick. I had the opportunity to orchestrate most of those songs without demoing at all.

It's much better, because when you demoed with samples – particularly then when sampling was new – you had to make your arrangement and make your samples sound good. You weren't really free to write what you wanted to write. You were free to write what you could make work with samples. Then, once they got used to that, you had to reproduce it.

Do you have any projects for the rest of 2024 and into 2025 you can tell us about?

Hercules, which opened in Hamburg, is opening on London's West End next spring. I imagine my work will begin in December. It’s a great pleasure for me to be co-orchestrating the show with Joseph Joubert.

I've reached the age where half a show is really better than a whole show. I really enjoyed doing those orchestrations because they weren't as legit as what people normally had me do. Most of them were quite poppy. They came out very well and it was a very gratifying experience. I'm happy that it's going on.

We had done Aladdin in Hamburg in 2014 at the same theatre. In Germany, musicians are hired by the theatre. So, it was like a reunion.

I'm hoping that Hercules winds up being as big as Beauty and The Beast. No way to know if it will be, but it sure will be nice if it is.

I'm not looking for work in the interim. I worked very hard on Soft Power, and I can use a few months to relax.

Special thanks to Signature Theatre's Marketing Manager and Publicist Zachary Flick for his assistance in coordinating this interview.

Theatre Life logo designed by Kevin Laughon.

Comments

Videos

.gif)